The New York Times has called President Barack Obama the “regulator in chief.” Why?

The nation’s 44th president has led a regulatory assault on American business - specifically the $748 billion trucking industry.

In fact, during Obama’s two terms, Washington regulators have produced 600 major regulations with dozens more in the pipeline. And while not all of them affect trucking, of course, many do.

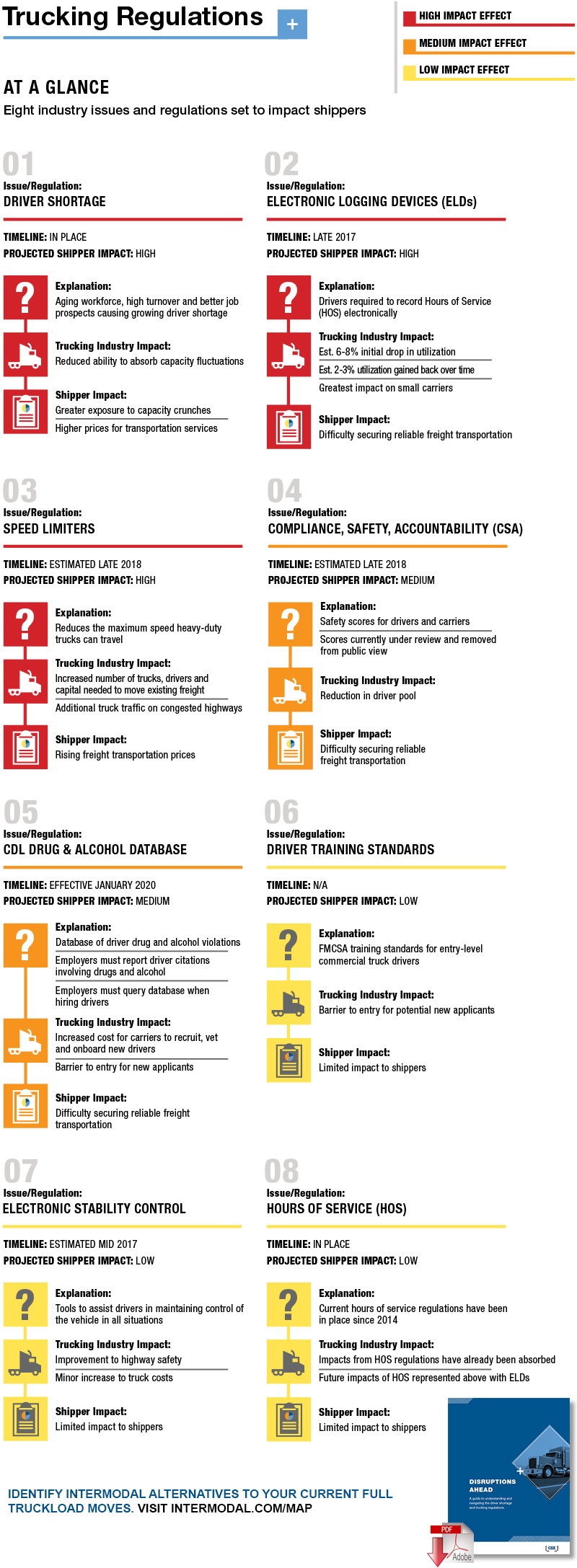

They cover everything from emissions, safety reporting of accidents, hours-of-service (HOS), electronic onboard recorders, entry-level training, fuel-mileage standards, overtime pay, hair follicle testing for drug cheaters, speed governors, sleep apnea testing, diesel emission standards and visas for foreign workers who might ease the truck driver shortage.

While economically deregulated since 1980, interstate trucking is still massively regulated at the federal level by the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Department of Labor, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and scores of other units within other departments. In the meantime, states are nearly as aggressive.

Thomas J. Donohue, president and CEO of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and former chief of the American Trucking Associations (ATA), sees all the fine print coming out of the agencies in Washington and sums it up in three words: “A regulatory tsunami.”

In 2016, George Washington University’s Susan Dudley and Washington University’s Melinda Warren conservatively estimated that 279,000 federal workers staff regulatory agencies. To put this in perspective, in 1960 at the end of President Dwight Eisenhower’s second term, that number was just over 57,000.

William Kovacs, U.S. Chamber senior vice president for Environment, Technology & Regulatory Affairs, says that Congress is mostly at fault. He says Washington bureaucrats feel they need to do something to justify their jobs, and trucking appears to be a ripe target.

The result in trucking is that the industry is not only being hit with new and creative rules, but it’s seeing a backlog of other rules such as the HOS 34-hour restart provision awaiting final word from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

Whatever happens on these various rules, one thing is certain: shippers will pay more. That’s because in the thin-margin trucking business - carriers make on average 3% to 4% margin even in good years - there’s no place else to absorb these costs.

“It’s going to feel like a tremendous weight to bear because we have everything coming at us,” says Derek Leathers, president and CEO of Werner Enterprises, the nation’s 4th largest truckload (TL) carrier. “But to the extent that you can get out in front of regulations, it can work to your advantage.”

Analysts are warning that while the large mega-carriers have the savvy leadership and economies of scale to survive, other less well-capitalized carriers may fall victim to the regulatory onslaught.

“Looking ahead, smaller carriers may struggle under the weight of forthcoming regulations, competition for drivers and their reliance on truck brokers,” says John Larkin, veteran trucking analyst for Stiefel Inc. “Some slow consolidation may be inevitable as small carriers decide it’s not worth continuing in business given a challenging spot market and the coming requirement to operate in absolute compliance with federal regulations.”

With this heated environment in mind, let’s take a deeper dive into the regulatory maze facing truckers and work to figure out which new rules will be making the most impact on shipper transportation strategies and budgets.

“Black Boxes”

Electronic logging devices (ELDs), also known in trucker parlance as “black boxes,” are about the size and weight of a Bible and are abhorred by many drivers and adored by most large trucking fleets.

Major truck fleets have long hinted that some independent drivers fudge their legal hours of service using paper logs - hence the reason that larger fleets pushed for mandatory ELDs. However, the Owner-Operator Independent Driver Association (OOIDA) has sued the DOT on grounds that the devices don’t help safety and merely are another tool for “harassment” of drivers. The case is pending in the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals.

ELDs are not necessarily a new development. In fact, the 28 European Commission countries as well as some Central and South American countries currently require them. Costing about $300, these tamper-proof devices are in line to be required on all trucks in the United States by the end of next year - and major fleets say they’re worth every dollar.

“Simply put, it makes us safer as an industry,” says Chuck Hammel, president of less-than-truckload (LTL) carrier Pitt Ohio. He adds that the immediate productivity hit in eliminating illegal hours is between 7% and 10%, but that can be mitigated over time as carriers learn what they can and cannot do.

“ELDs provide many operational advantages internally,” says Hammel. “First and foremost, it gives you visibility as to when the driver is moving or sitting and exactly how many hours the driver has left to drive. This is critical information to have when scheduling pickups.”

Big carriers such as Swift Transportation, Schneider, Werner and others have been using ELDs for many years. In fact, Werner was the first large carrier to convert from paper logs to ELDs in 1998. “ELDs don’t make a fleet safer by themselves,” says Werner’s Leathers. “That comes through investments in safety training and creating a culture of safety within the organization. But it assures that shippers, carriers and drivers are on the same page when it comes to expectation of transit times.”

The Emissions Game

A new Class 8 truck cost roughly $80,000 a decade or so ago. Today, that same truck costs roughly $140,000 before any fleet discounts for multiple orders.

The 2017 model Peterbilt, Freightliner, Paccar, Volvo or Mercedes all come outfitted with world class emissions controls, costly electronics and other devices that OEMs say have eliminated as much as 98% of particulate matter into the atmosphere.

As Phase 2 of National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and EPA truck emissions regulations are set to start in the coming years, carriers and government officials say shippers ought to get ready to help pay for them. The EPA estimates these Phase 2 rules, which start on Jan. 1, 2018, for trailers will be followed by tractor regulations coming in three rollouts through 2027. The EPA says that the move is projected to cut greenhouse gases (GHG) 13% by 2021, 20% by 2024 and 25% by 2027.

However, it will come with a considerable price. The cost for the trailers-only rule in 2018 is estimated at $1,090, but the per-vehicle tractor costs will be $12,300 by 2027.

“These standards are ambitious and achievable, and they’ll help ensure that the American trucking industry continues to drive our economy - and at the same time protect our planet,” says Gena McCarthy, EPA administrator. “We expect these will drive innovation as well as protect the air we breathe.”

ATA officials contend they were “cautiously optimistic” that the new rules were workable, and that the 10-year phase-in period for the regulation would not be unduly disruptive to fleets and manufacturers.

“While today’s fuel prices are more than 50% lower than those we experienced in 2008, fuel is still one of the top two operating expenses for most trucking companies,” says ATA president and CEO Chris Spear, noting that ATA worked with Washington officials for the past four years to ensure that these fuel efficiency and greenhouse gas standards took into account the wide diversity of equipment and operations across the trucking sector.

“ATA developed and adopted a set of 15 guiding principles to serve as our major parameters for inclusion in the final rule,” says Glen Kedzie, vice president and energy and environmental counsel for the ATA. “We’re pleased that our concerns such as adequate lead-time for technology development, national harmonization of standards and flexibility for manufacturers have been heard and included in the final rule.”

But some carrier executives are skeptical of the EPA because of past problems with emissions regulations. John White, chief marketing officer for U.S. Xpress, says that the recent EPA-required changes in 2010 and 2012 resulted in some problems with engine filters and after-market treatments.

“All of the larger fleet operators accelerated our trade-in cycles because of down time and maintenance,” says White. “We dumped a lot of low mileage trucks onto the used truck market place.”

Speed Limiters, and More

What else is coming down the regulatory pipeline for trucking? For one, the government wants to put the brakes on the trucking industry. In fact, NHTSA and the DOT are proposing speed governors on new trucks with a maximum speed probably around 62 to 68 miles per hour, although it says it’s waiting for public comments to determine the exact highest speed.

Transportation secretary Anthony Foxx says that the safety measure could save lives and more than $1 billion in fuel costs each year; and, more importantly for truckers, the rule wouldn’t require the retrofitting of the approximately 3.5 million older tractor-trailer trucks on the highways.

“It’s a reasonable rule,” says Leathers. “We have speed limiters set at 65 mph, but they can be brought down to 62.” The key, he says, is to find the correct relationship between safety and fuel economy.

Since 2006, the ATA has adopted a policy in favor of limiting the maximum speed of new trucks to 68 miles per hour. The proposed ruling sets up yet another fight between owner-operators, which are against the governors, and the organized trucking industry, which is in favor of the speed limiters.

OOIDA says that according to DOT data, less than 8% of fatal crashes involving trucks are speeding-related, compared to almost 30% for passenger vehicle crashes. The owner organization also says that speed limiters for trucks would result in a significant speed differential between cars and trucks on roads like interstate highways.

Safety advocates contend that the safest highways are those where traffic travels at the same or similar speeds. For every speed differential of 1 mile per hour between vehicles, the likelihood of interaction increases. Trucking executives agree that speed uniformity on the highways is key. “Speed should not be a competitive landscape,” adds Leathers.

Road Ahead

State regulators are not far behind Washington bureaucrats when it comes to causing heartburn for truckers. Trucking executives say that state-specific regulations in California and elsewhere governing meal breaks, overtime pay and other issues threatens to create a “patchwork” of inefficient state regulations affecting interstate commerce.

Already, some LTL carriers have instituted a “California surcharge” of 2% or more on shipments in and out of the Golden State. As states get more aggressive in targeting the trucking industry for taxes and other fees, carriers worry that they’ll be ripe targets or even more creative rules.

“It’s an onslaught,” adds Werner’s Leathers. “It’s more than I’ve seen in a lifetime, and it just keeps on coming. They seem very efficient in finding ways to legislate things that cannot be legislated.”

Article topics

Email Sign Up